Preston Richey

Lessons in Stealing My Boss' Voice

The first time I heard audio generated with Lyrebird I was in my car on the way home from Barkley, listening to NPR. I remember this distinctly. The story was about a Canadian start-up using machine learning to capture and then mimic anyone’s voice, synthesizing novel phrases in a spookily convincing simulacrum. It was one of those moments that have been happening more and more recently, where feats previously only featured in sci-fi are brought into actuality. You knew the future would get here eventually, but had no idea how soon it’d actually be.

The story played audio synthesized with Lyrebird models trained on both Barack Obama and Donald Trump. To be clear, I wasn’t fooled entirely — phrases generated with the system still somewhat tinny and robotic, lacking convincing phrasing and execution. Nevertheless, there’s no doubt about who the model is imitating. Just like the computer graphics of the 90’s, Lyrebird’s synthesis is convincing enough to be a harbinger of a future where it’s nearly impossible to distinguish the real from the artificial.

This being the case, the technology was a natural shoe-in for Moonshot’s recently completed exhibit about Conversational Interfaces, which we’ve named Marco Polo. For more information about the exhibit as a whole, here’s a quick write-up by Barkley’s SVP of Innovation, Mark Logan.

This being the case, the technology was a natural shoe-in for Moonshot’s recently completed exhibit about Conversational Interfaces, which we’ve named Marco Polo. For more information about the exhibit as a whole, here’s a quick write-up by Barkley’s SVP of Innovation, Mark Logan.

The Surprising Power of Asking Nicely

After deciding that we wanted to showcase Lyrebird in our exhibit, the next step was to figure out how. Lyrebird has a functional demo available for anyone to try out: simply record a minimum of 30 pre-selected sentences, and voilà, you can start synthesizing phrases with your artificial voice. You can keep on recording sentences to improve accuracy — 30 sentences is okay, 50 sentences sounds pretty good, and 100 sentences sounds even better. We came up with the idea of getting Jeff King, Barkley’s CEO, to train a model and then giving Barkley partners the opportunity to make their boss say whatever they want. What could go wrong?

The only issue is that we were confined to generating audio on Lyrebird’s web site, as opposed to a separate experience designed to fit with the rest of the exhibit. Rather than using a text input, we wanted to allow users to speak a phrase, have the audio transcribed before being generated by Lyrebird, then played back to the user.

After a few failed attempts at other solutions, I realized I hadn’t tried the simplest one: reaching out to Lyrebird and asking for API access. I wrote a quick email to the address on their contact page and a few days later had a response in my inbox asking for a time to have a quick phone call. After making contact, I described how I would be using the technology, and to my surprise, we were granted beta access to their developer API! This would allow us to train a voice model, then make an API call to generate audio on the fly — exactly what we needed.

Capturing A Voice

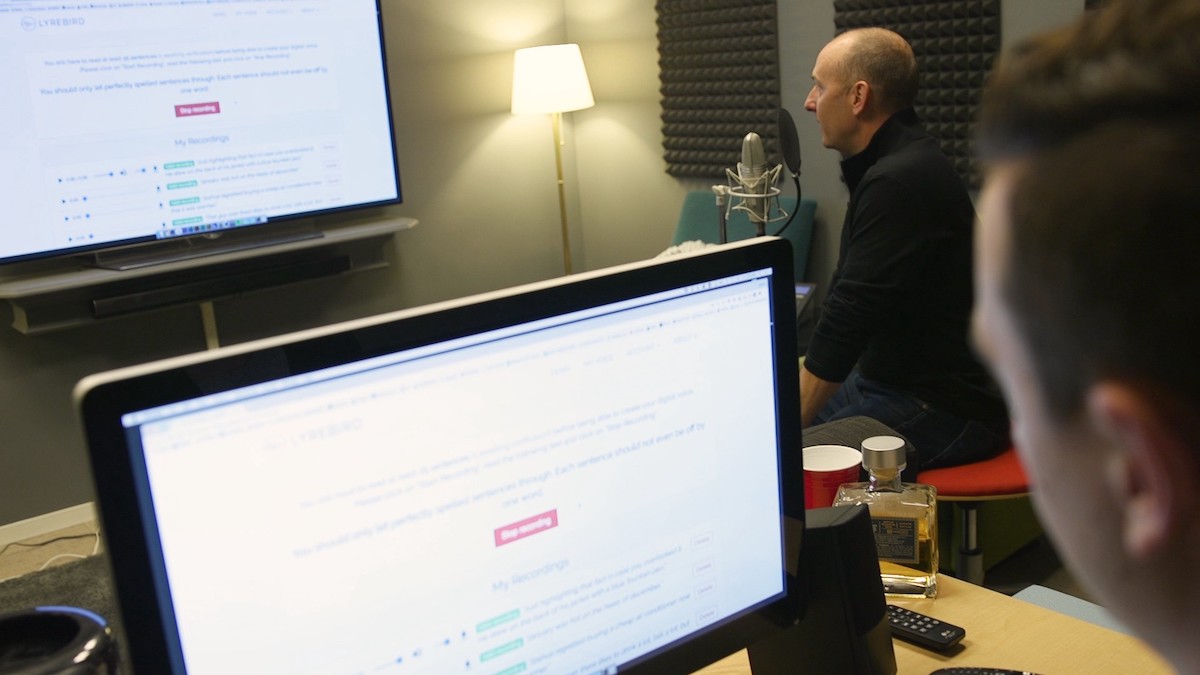

The next step was to actually train our voice model. We booked some time with Jeff to come in and record with a nice microphone in the production team’s sound-proof edit bay. Training a model with Lyrebird is incredibly simple but tedious: just press ‘record’, then read aloud a sentence given to you by Lyrebird (e.g. “That’s a sophisticated mechanical system! We want to disperse the core from the hull”). In about 15 minutes we hit the minimum of 30 sentences, but we kept on recording to try and get the best model we could. After 100 sentences, ‘fake Jeff’ was sounding pretty convincing.

Pulling It All Together

After training our voice model, the last step was to build out the exhibit experience. We liked the idea of having a minimal interface — press a button, say a phrase, then hear the phrase spoken back in Jeff’s voice. Using Lyrebird’s API ended up being easy to work with and well documented. We ended up using Google Cloud Speech API for audio transcription, which was quick and reliable. A bit of Arduino code allowed a button to interface with the main application’s Node.js back end via a USB port.

Despite being an exciting and impressive product, Lyrebird still has a way to go. While the 100 sentences we recorded with Jeff were more than enough to generate most longer phrases convincingly, for some reason Lyrebird struggles with shorter phrases and single words.

For example, “My name is Jeff” trails off with a robotic slurring at the end:

Yet longer phrases sound convincing, even with difficult words like ‘Orangutan’ and ‘Worcestershire’ (neither of which appear in the original source recordings):

Cadence and emphasis also leave something to be desired. For example, the model struggles with counting:

There also seems to be a persistent low-volume buzz in all of the recordings. This can certainly be stripped out with post-processing, and I assume it will eventually be removed from the generated audio, but for now it can sometimes be distracting. Here’s a demonstration of raw compared to post-processed audio:

Moving Forward

Audio synthesis technology like Lyrebird is on the cusp of being convincing enough to be scary. It’s not quite there just yet, but in the next few years we collectively will have to confront the fact that any audio may very well be falsified.

On the one hand, it will change the practice of advertising and video / audio production forever. Imagine if you no longer need to hire voiceover artists and can simply design the perfect artificial voice with which to synthesize voiceover or narration. Such advancements will be a boon for creative agencies and anyone involved in video production, but may put some voice actors out of business. Technologies like Lyrebird could also allow us to record our voices for posterity, allowing future generations to converse with their departed ancestors.

On the other hand, there are obvious and vital implications for the way that we understand and judge news reporting. With accusations of fake news at an all-time high, it will only become more difficult to distinguish the actual from the synthesized. Furthermore, parallel advancements in video synthesis will be married with audio synthesis technology to create convincingly faked video content. These techniques are already being used to do everything from face-swapping Nicholas Cage into random movies to creating fake celebrity porn (sfw).

While developers of these powerful technologies are responsible for taking all reasonable steps to make sure that their products are used ethically and legally, ultimately the onus falls on us to reinvestigate as a society how we decide what is real and what is fake. Just as the advent of Photoshop didn’t irreversibly corrupt photojournalism, I believe we will establish reliable techniques to make sense of the media we consume. We simply must remember not to blindly believe our eyes (or in this case, our ears).

This post originally appeared on Moonshot’s Medium.